Email has certainly become run-of-the-mill since its inception circa 1972. Little did Ray Tomlinson, the man credited with inventing email, know that over 3.7 billion people would be emailing in 2018! The rise of email has had to do with our shared belief that it’s more efficient than face-to-face meetings and phone calls. Moreover, it has enabled information sharing with more diverse sources when compared to the traditional single-channel memos (remember those!?). An email was once seen as the ultimate savior in connecting more people more of the time. We, of course, know better now in the age of “digital overwhelm”…

The Email Paradox

Alas, the not-so-nice side of email has reared its ugly head. We often hear the cries of “overload” when we think about our inboxes that never seem to empty. For most today, it’s impossible to get emails down to “zero”. And even if it happens, it is but a moment’s celebration before new messages start pouring in.

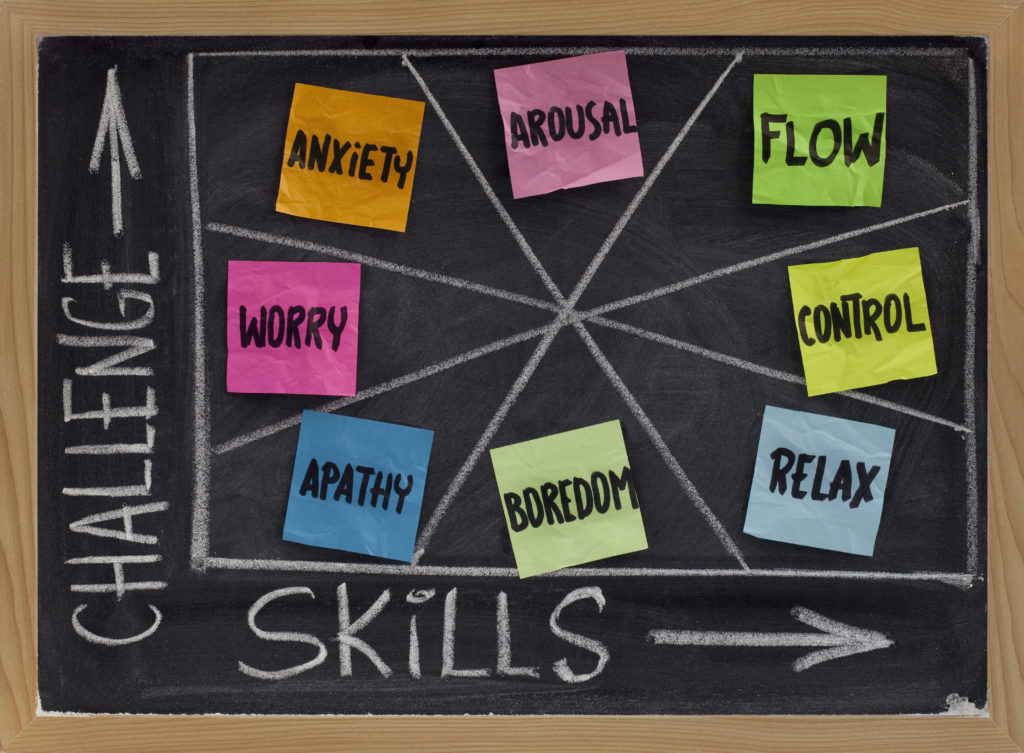

“Email overload” can be correlated with the number and the length of emails received, and the time it takes to process and respond to each. The immediacy of receiving emails has caused the undue pressure we feel to respond quickly. It is also the culprit for generating many unanticipated tasks in our calendars. Email causes innumerable interruptions daily; it makes us feel out of control when it comes to managing our time. Finally, email forces us to switch tasks continuously and challenges us to enact different roles simultaneously. We, in effect, lose our sense of focus and flow.

Human beings have a limited capacity to receive, interpret, assimilate, and apply information. When our limits are exceeded, our cognitive performance declines. This results in the inability to make decisions, prioritize, or organize information, thoughts, and processes. Hence lies the “email paradox”. On the one hand, email has facilitated widespread information distribution and reduced information delays. On the other, it has overwhelmed our processing capabilities and brought about feelings of stress, inefficiency, demotivation, and confusion.

The Effects of Sending “One to many”

Email volume is dependent on many factors including job characteristics and organizational culture. An average employee will receive slightly more than twice the number of messages they send. With our ability to send “one to many”, the marginal cost per message experienced by senders is dramatically reduced when compared to traditional tools like “snail mail”. As a result, senders enjoy a disproportionate share of the email benefits while email receivers bear the brunt of the proverbial costs.

A typical employee will receive upwards of 350 email messages per week (70 messages per workday), while an executive will receive upwards of 300 messages a day! On average, one-third of messages received are considered unnecessary and can be quickly deleted. The other necessary messages will require anywhere from 2-5 min to process as they need to be read and responded to with attention to proper word choices, correct spelling and grammar, and the correct recipient list. This all takes time. In fact, the average employee will spend approx 2.9 hours/ day on email while an executive can spend upwards of 10.8 hours!

Recipients spend a lot of their time and energy in reading and responding to another’s information request. They also tend to interrupt their own work to continuously monitor incoming emails. They do so to satisfy senders’ expectations of a timely reply.

The Financial Impact of Email

According to some studies, employees will take 24 minutes on an average to get back into the groove of their work after checking email. They will also check email at least 50 times per day and use instant messaging. These numbers are steadily increasing as we incorporate the “internet of things” into our lives. The average worker will lose at least 6 hours per week to email interruptions and 2 hours per week to processing unnecessary email. This is a total productivity loss of 8 hours per week just on email alone. It comes out to 392 hours per year—per employee. For an organization with 50,000 employees, this can translate to an approximate loss of $1B in productive employee time!

Email and Its Effects on Cognitive Performance

In addition to corporate financial losses, other employee productivity parameters are also affected. IQ scores have been used historically by psychologists when comparing performance in distracted versus non-distracted states. They refer to the degradation in focal task performance as “dual-task interference” when an individual tries to perform a second task simultaneously. The average employee, while distracted by email, exhibits twice the degradation in IQ scores during task execution. This is the same IQ scores exhibited by someone who has just smoked marijuana!

In the tech-driven world where we have the increased pressure to “empty our inboxes”, we are forever multitasking. You can see this in checking email while in meetings or texting while driving. It starts in the morning when checking our social feeds while, at the same time, feeding our dog or going to the bathroom. We kid ourselves into believing that doing multiple tasks at the same time somehow increases our productivity. The sad reality is that studies completely disprove this belief.

What’s the Truth?

“High media multitaskers” who frequently engage in five or more simultaneous information streams score poorly on standard judgment, recall and reaction times when compared to “low media multitaskers”. Outside of media, studies measuring the effects of high task switching show similar results. The scary thing is that multitaskers and frequent task switchers usually feel more confident about their performance than those engaging with less divergent efforts. Decision-makers, who are bombarded with more information, tend to feel more confident about their decision making than those with access to less information. Sadly, the “information rich” people usually end up making worse decisions. Continuous churning through email has given us a false sense of control over our work. We have also internalized the cultural belief that more information is better, safer and more reliable. Little did we know that besides the possibility of “paralysis by analysis”, more information has actually numbed our higher faculties.

It is recognized that an individual’s information-processing capacity will vary over time. It can fluctuate with mental and physical energy levels as well as other external conditions. Our natural limitations for information perception, interpretation and judgment are exacerbated by our common email practices of constant interruptions, task-switching, and multitasking. Our daily routines of consuming social media, text messages, and email has eroded our capacity to assimilate and apply new knowledge, to successfully accomplish tasks, and to make decisions. Unfortunately, our boosted self-confidence, buoyed by the banks of “at your fingertips” information, delays our recognition of underperformance due to overload.

What is Overload?

When we finally realize that, despite our best efforts, we are underperforming, the tragic reality of “digital overwhelms” sets in. Information overload is a multi-dimensional experience incorporating factors such as time, tasks, relationships and a sense of control, or lack thereof. In technical terms, overload can be defined as a condition where the cognitive demands associated with information processing exceeds an individual’s information processing capacity. Our cognitive performance decline can be detected by our inability to make accurate “signal-noise” distinctions and situation assessments. In addition, we become less efficient in making high-quality decisions. When we hit the “overwhelm” stage, it can affect our long-term memory, attention levels, comprehension, retention, and recall. It can also result in an individual experiencing exhaustion, poor physical health, reduced relationship satisfaction, and other psychosomatic symptoms.

How Email Can Contribute to Social Overload

Another reality today is “digital overwhelm” at the social level. Social overload can occur when the number and variety of social exposures and the associated social information received exceeds an individual’s interaction capacity. In traditional office environments, workers use physical barriers—walls, doors and the distance between employees—as ways to segregate, contain and “serialize” their interactions and their accompanying role demands. These structures, in effect, created the container that people needed to protect their personal boundaries and to give them a refuge in which to recharge.

With the new world of “hoteling”, reservable workspaces, virtual offices, and co-working spaces, there is less protection and more pressure to be available at all times. Interestingly, people living in more densely-populated urban areas have a tendency to unconsciously contract the physical range of their social circle, effectively limiting their number of relationships and day-to-day encounters. This is their way of creating “space” in their day in order to recharge and decompress.

These same individuals, in contrast, will increase the density of their computer-mediated world in order to further expand their circle of online encounters. No wonder we see individuals engrossed in their phones even when in the midst of family members or colleagues. We become more attached to our virtual world and social connections as we have unconsciously detached from the real world in order to protect our limited capacity for social interaction.

Drawing the Line

The lines between when and how to engage in professional social media sites, such as LinkedIn, social sites, such as Facebook and Instagram, and company chat rooms, such as Yammer or Slack, have blurred. We are spending time at work updating our Snapchat account and time at home connecting with colleagues from overseas. In practice, the boundaries between these domains are becoming less distinct, further increasing the social load employees encounter during work hours. In any given hour of the workday, one may receive messages from one’s boss, spouse, client, child’s soccer coach, vendor, child, dentist, friend, organization, and former classmate, each with a unique request and a particular time horizon for responding. Not only do we have to cognitively-process the content of the message and reply appropriately, but each interaction must be prioritized within the broader ecology of one’s relational life. Work-life balance has transmuted into work-life integration.

How to Assess and Manage Email Overload

There are a series of ways to monitor and combat email overload. The first step is to take an inventory of the number, length, type, and importance of emails that are received within a specific period of time. Next, one must determine the amount of time that it is taking to process each message type, and the time required to complete any tasks necessary to respond to the received messages. Other dependent variables include the average time per day spent processing email communication, both within and outside of regular work hours, the average elapsed time between message receipt and message response for each message type, and the proportion of each day’s messages that go unread.

Evaluation is Important

Descriptive statistics of an employee’s interaction partners over the course of a workday and the number of different social contexts represented by these contacts should also be evaluated. Subjective data, such as ratings of perceived stress or feeling focused versus fragmented at intervals throughout the study period (e.g. hourly, daily) should be evaluated and tracked. These ratings would then need to be mapped against the social density of the interval (i.e. the number of unique message senders and the number of discrete social contexts represented by that interval’s message senders).

It could also be useful to measure the time required to compose response messages and the appropriateness and tone of the language used. Did they remember to add the attachment they mentioned? Did they include the right individuals in the recipient list? As individuals become socially overloaded, they may become less adept at making role transitions. Consequently, it may require an employee longer to compose a relationally-appropriate response, or they may respond quickly but without making the appropriate shifts in vocabulary and tone. It is important to note that when employee’s interaction density increases due to multiple professional and personal roles, they can have a more difficult time with “recovery” strategies. This can lead to less ability to psychologically detach, relax, and master their feelings of autonomy.

Let’s Talk About Strategies for Overcoming “Digital Overwhelm”

There are a number of strategies that organizations can incorporate as a means to manage email overload, many with varying degrees of effectiveness and impact. A few of these are:

- Filtering and message threading (e.g. separate urgent vs. non-urgent emails) – see SaneBox

- Creating organizational email policies incorporating communication restrictions (i.e. no email on weekends)

- Setting rules around subject lines, “to” vs “CC” prioritization, batch processing, and reminder follow-ups

- Writing guidelines for selecting the media to use for the type of communication; for example, use instant messaging for task-related communication only and reserve email for non-time-sensitive content, or to document decisions

- Setting rules on how and when to use “out of office” or “do not disturb” notifiers

Interestingly, companies are also leveraging synchronous channels such as web meetings to create a sense of proximal interaction, which is often missing in our virtual world. People still want to feel connected to the greater ecosystem in which they work and with their colleagues, they are collaborating with. Working in vacuums or in “transient offices” where the average employee feels like a displaced person, has caused many workers to migrate to coffee shops in order to stay motivated and connected with other human beings.

The Exciting Future of Digital Communication

Increased numbers of company-branded portals, used to incorporate threaded projects and to capture tribal knowledge among colleagues and customers, have surfaced recently. These are excellent asynchronous forums that reduce email overload. This is because project work can be captured in private, company-branded, online spaces. Convenient, asynchronous communication, sharing, and collaboration can occur unobtrusively. They assist in giving us processing time to respond without feeling the pressure to react to an email. These kinds of portals provide a balance between adequate social density while maintaining individual boundaries and structure to recharge. As a result, private online portals have dramatically increased the level of customer engagement and brand advocacy.

An email will continue to drive our work and life. It is here to stay. And we can’t ignore that it has expanded our data exchange to a new level beyond belief. As we step on the precipice of artificial intelligence, the need for rapid information exchange and big data analysis becomes even more pronounced. It is up to us now to leverage these tools, email included so that they optimize our potential and don’t deter our personal and professional progress. By taking active measures to monitor our sources of information, work, and social overload, we can create solutions to combat “digital overwhelm” and to protect our decision making prowess.

References

Allen, D. & Wilson, T. D. (2003) Information overload: context and causes. The New Review of Information Behaviour Research, 4, 31– 44.

Allen, D. K. & Shoard, M. (2005) Spreading the load: mobile information and communication technologies and their effect on information overload. Information Research, 10, paper 227. Retrieved January 15, 2011 from http:// InformationR.net/ ir/ 10-2/ paper227. html.

Dabbish, L. & Kraut, R. (2006) Email overload at work: An analysis of factors associated with Email Strain. Proceedings of the 2006 Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work.

Derks, D. & Bakker, A. B. (2010) The impact of e-mail communication on organizational life. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 4. Retrieved from http:// cyberpsychology.eu/ view.php? cisloclanku = 2010052401& article = 1.

Eppler, M. J. & Mengis, J. (2004) The concept of information overload: A review of literature from organization science, accounting, marketing, MIS, and related disciplines. The Information Society, 20, 325– 344.

Hemp, P. (2009) Death by information overload. Harvard Business Review, September, 83– 89.

Heninger, W. G., Dennis, A. R. & Hilmer, K. M. (2006) Individual cognition and dual task interference in group support systems. Information Systems Research, 17, 415– 424.

Jacoby, J. (1984) Perspectives on information overload. Journal of Consumer Research, 10, 432– 436.

Jarvenpaa, S. & Lang, K. (2005) Managing the paradoxes of mobile technology. Information Systems Management Journal, 22, 7– 23.

Middleton, C. (2007) Illusions of balance and control in an always-on environment: A case study of Blackberry users. Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, 21, 165– 178.

Richtel, M. (2008) Lost in e-mail, tech firms face self-made beast. The New York Times, June 14, 2008. Retrieved January 15, 2011 from http:// www.nytimes.com/ 2008/ 06/ 14/ technology/ 14email.html.

Spivak, N. (2004) The emerging problem of ‘social overload’. Weblog post Jan 25, 2004. Retrieved January 24, 2011 from http:// novaspivack.typepad.com/ nova_spivacks_weblog/ 2004/ 01/ the_emerging_pr.html.

Sproull, L. & Kiesler, S. (1991) Connections: New ways of working in the networked organization. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Tarafdar, M., Tu, Q., Ragu-Nathan, T. S. & Ragu-Nathan, B. S. (2011) Crossing to the dark side: Examining creators, outcomes, and inhibitors of technostress. Communications of the ACM, 54, 113– 120.

Thomas, G. F., King, C. L., Baroni, B., Cook, L., Keitelman, M., Miller, S. & Wardle, A. (2006) Reconceptualizing e-mail overload, Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 20, 252– 287.

Williams, M. L., Dennis, A. R., Stam, A. & Aronson, J. E. (2007) The impact of DSS use and information load on errors and decision quality. European Journal of Operations Research, 176, 468– 481.